Exploring Benjamin Franklin's Scientific Collaborations

Written on

Chapter 1: The Scientific Network of the 18th Century

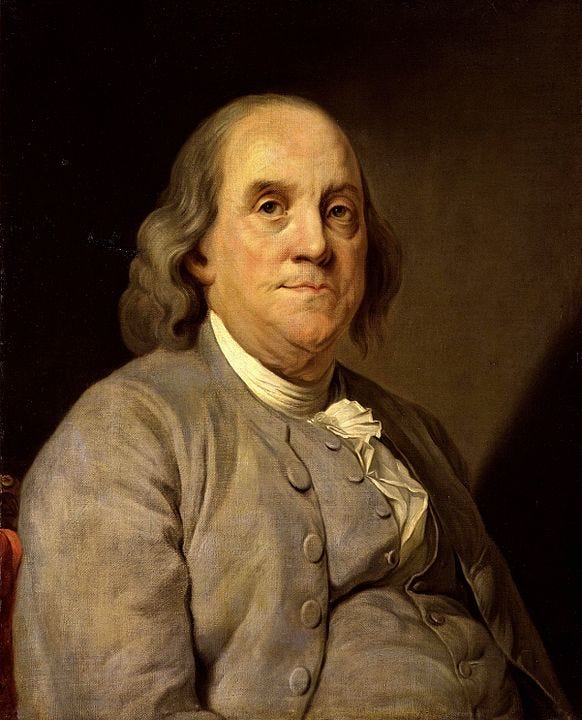

Benjamin Franklin is widely recognized as a remarkable scientist. Schoolchildren across America learn about his inventions, such as bifocals and his famous kite experiment in a thunderstorm. Often depicted as a solitary innovator, Franklin was actually part of an international community of amateur scientists. The notion of a professional scientist as we know it today was nonexistent during that era. Much of the scientific work was carried out by affluent amateurs who would publish their findings, yet often preferred to share their experiences and discoveries privately through correspondence. Over his lifetime, Franklin authored numerous scientific letters, but one particular correspondence exemplifies how this global scientific community operated in the late 1700s.

Franklin's letters illustrate the collaborative spirit of science in his time.

Section 1.1: A Letter from Jan Ingenhousz

In 1783, Franklin received correspondence from Jan Ingenhousz, a highly respected scientist known for his work in various fields, including smallpox inoculation and the discovery of photosynthesis. Ingenhousz had previously been the court physician for the Empress of Austria after successfully immunizing her against smallpox. In his letter, amidst discussions about smallpox and troublesome printers, Ingenhousz recounted an incident that would catch Franklin's interest due to his own research on electricity. While Franklin reported experiencing electrical shocks without harm, Ingenhousz had suffered a severe electric shock that left him unconscious.

Subsection 1.1.1: The Risks of Experimentation

Ingenhousz's accident occurred while he was experimenting with a Leyden jar, an early device that stored static electricity. While charging the jar, he inadvertently got too close to the conductor, resulting in an electrical spark that knocked him out cold. Upon regaining consciousness, he found himself temporarily disoriented, struggling to remember his home address. After finally returning home, he discovered that he had forgotten how to write. Remarkably, the following day he felt an enhanced clarity of thought.

Chapter 2: A Global Scientific Community

The collaboration between a Dutch scientist residing in London and an American scientist living in Paris illustrates the interconnectedness of the scientific community in the 18th century. This network extended beyond the West, incorporating informal scholarly exchanges in the Islamic world and the Far East, where Indian scholars contributed to advancements in British astronomy.

In the video "Secrets of Ben Franklin's Long and Useful Life," viewers gain insights into Franklin's life and contributions to science, including his connections with contemporaries like Ingenhousz.

Section 2.1: Innovative Ideas from Collaboration

Ingenhousz's electrical accident inspired him to consider the therapeutic potential of electricity in treating mental illness. He proposed that administering electric shocks to patients might alleviate their conditions. Both Franklin and Ingenhousz presented this idea to physicians of the time. Scholars Sherry Ann Beaudreau and Stanley Finger argue that some medical practitioners adopted this approach and recorded notable successes.

The video "Benjamin Franklin, The Writer" delves into Franklin's literary contributions and his correspondence with fellow scientists, highlighting the importance of communication in scientific progress.

Conclusion: The Community of Science

The letters exchanged between Franklin and Ingenhousz reveal that the practice of science was not solely the endeavor of isolated researchers, but rather a collaborative effort among amateur scientists who relied on personal connections for knowledge sharing. The history of science is just as compelling as the scientific discoveries themselves.

References

Beaudreau, Sherry Ann, and Stanley Finger. 2006. “Medical Electricity and Madness in the 18th Century: The Legacies of Benjamin Franklin and Jan Ingenhousz.” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 49 (3). Johns Hopkins University Press: 330–45.

“Empires of Knowledge: Scientific Networks in the Early Modern World | Reviews in History.”

Schaffer, Simon, Lissa L Roberts, Kapil Raj, and James Delbourgo. 2009. The Brokered World: Go-Betweens and Global Intelligence, 1770–1820. Science History Publications.

“‘To Benjamin Franklin from Ingenhousz, 15 August 1783,’ Founders Online, National Archives, Https://Founders.archives.gov/Documents/Franklin/01-40-02-0292. [Original Source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, Vol. 40, May 16 Through September 15, 1783, Ed. Ellen R. Cohn. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011, Pp. 475–484.].” n.d.